Session 7 – notes

Here are some resources for the Monday lecture in week 4. I spent most of the time going through the slides and working though some examples – you can see the slides here.

Finishing what we started the previous lecture

Last time we began implementing a REST service (or, rather, a JSON over HTTP service) for our college application database.

We had already implemented the following endpoints:

GET /ping: just to see if the service is aliveGET /students: first we only returned all students, later we added querying, so that we could filter out students by name or minimum gpaGET /students/<s_id>: fetches a specific student

You can see the notes to the previous lecture for more details, here's where we ended up then (I've added the urllib.parse calls and trace call to our connection which I talked about at the beginning of this lecture):

from bottle import get, post, request, response, run

from urllib.parse import quote, unquote

HOST = 'localhost'

PORT = 4567

db = sqlite3.connect("colleges.sqlite")

db.set_trace_callback(print)

@get('/ping')

def get_ping():

response.status = 200

return 'pong'

@get('/students')

def get_students():

query = """

SELECT s_id, s_name, gpa

FROM students

WHERE TRUE

"""

params = []

if request.query.name:

query += "AND s_name = ?"

params.append(unquote(request.query.name))

if request.query.minGpa:

query += "AND gpa >= ?"

params.append(request.query.minGpa)

c = db.cursor()

c.execute(

query,

params

)

response.status = 200

found = [{"id": id,

"name": name,

"gpa": grade} for id, name, grade in c]

return {"data": found}

@get('/students/<s_id>')

def get_student(s_id):

c = db.cursor()

c.execute(

'''

SELECT s_id, s_name, gpa

FROM students

WHERE s_id = ?

''',

[s_id]

)

found = [{'id': s_id,

'name': s_name,

'gpa': gpa} for s_id, s_name, gpa in c]

response.status = 200 if len(found) > 0 else 404

return {'data': found}

run(host=HOST, port=PORT)

It was now time to implement an endpoint for adding students, and since we're adding resources we'll use POST on the /student endpoint.

Last time we used JSON to return information from the server, this time we'll use JSON to send data to the server.

The POST request will have a body in which we put a JSON object with the information about the new student.

I used insomnia (there are many similar tools, many of them free, you can use whatever tool you like) to define the new student – we started out with:

{

"id": 916,

"name": "Bob",

"gpa": 3.8

}

Here we can decide for ourselves what name to give the fields, the names of the attributes in the tables of the database isn't seen outside the server, so we chose the simplest possible names.

But after talking about it a little, we decided that it would be better if the server generated the ids, since we otherwise might get problems with colliding ids. So, the JSON object we'll send to the server would be:

{

"name": "Bob",

"gpa": 3.8

}

To have the database generate the ids itself, I had to change the database a little, first generating a file with SQL commands to generate the whole database:

$ sqlite3 colleges.sqlite '.dump' > create-database.sql

(this is the same as opening the database inside sqlite3, running the .dump command, and copy its output into the file create-database.sql).

When we looked at the file create-database.sql, it started with:

PRAGMA foreign_keys=OFF; BEGIN TRANSACTION; CREATE TABLE students ( s_id INT, s_name TEXT, gpa REAL, PRIMARY KEY (s_id) ); INSERT INTO students VALUES(123,'Amy',3.899999999999999912); INSERT INTO students VALUES(234,'Bob',3.600000000000000088); ...

I changed the declaration of the s_id attribute in students to an INTEGER:

PRAGMA foreign_keys=OFF; BEGIN TRANSACTION; CREATE TABLE students ( s_id INTEGER, -- this used to be an INT s_name TEXT, gpa REAL, PRIMARY KEY (s_id) ); INSERT INTO students VALUES(123,'Amy',3.899999999999999912); INSERT INTO students VALUES(234,'Bob',3.600000000000000088); ...

and also changed the corresponding foreign key in applications (it's actually not necessary, but seems prudent):

...

CREATE TABLE applications (

s_id INTEGER, -- I also changed this

c_name TEXT,

major TEXT,

decision CHAR DEFAULT ('N'),

PRIMARY KEY (s_id, c_name, major),

FOREIGN KEY (s_id) REFERENCES students(s_id),

FOREIGN KEY (major, c_name) REFERENCES programs(major, c_name)

);

INSERT INTO applications VALUES(123,'Stanford','CS','Y');

INSERT INTO applications VALUES(123,'Stanford','EE','N');

INSERT INTO applications VALUES(123,'Berkeley','CS','Y');

...

The point of these changes is that a PRIMARY KEY defined as an INTEGER will 'autoincrement', and become a new unique value if we do an INSERT without defining it (see here, if you're curious).

As an alternative, I could have changed s_id to become a generated random string instead:

CREATE TABLE students ( s_id TEXT DEFAULT (lower(hex(randomblob(16)))), s_name TEXT, gpa REAL, PRIMARY KEY (s_id) );

Now I would have gotten ids like 254c164c1c68d842c98f2eb1e23de76f, but then the current applications in the database would have to be changed accordingly, so we used simple integers instead.

Now that we're getting database generated ids, we need a way to return them to the user of the server, and we used the INSERT ... RETURNING statement for that:

@post('/students')

def post_student():

student = request.json

print(student)

c = db.cursor()

c.execute(

'''

INSERT

INTO students(s_name, gpa)

VALUES (?, ?)

RETURNING s_id

''',

[student['name'], student['gpa']]

)

found = c.fetchone()

if not found:

response.status = 404

return 'could not create student...'

else:

db.commit()

s_id, = found

response.status = 201

return f'http://{HOST}:{PORT}/students/{s_id}'

We start by fetching the JSON object in the request, and bottle hands it to us as a dictionary, so we can fetch its parts using brackets, to get the "name" field of the object in student, we just call student['name'].

Once we've inserted the student, we need to do db.commit(), to ensure that the database is updated (we'll return to this next week), and then we return the url for the new student (it includes her id).

When we added Bob from insomnia, the server ran our post_student() function, first printing the student dictionary, and then showing what SQL statement we're actually running (thanks to the db.set_trace_callback(print) call we did above):

$ uv run app.py

Bottle v0.13.4 server starting up (using WSGIRefServer())...

Listening on http://localhost:4567/

Hit Ctrl-C to quit.

{'name': 'Bob', 'gpa': 3.8}

BEGIN

INSERT

INTO students(s_name, gpa)

VALUES ('Bob', 3.8)

RETURNING s_id

COMMIT

127.0.0.1 - - [09/Feb/2026 13:47:47] "POST /students HTTP/1.1" 201 34

...

In a REST service, we normally return the url for the newly created object in the header of the response, here we just send it back as a return value:

http://localhost:4567/students/988

which we can use to make a GET call to fetch the student with.

Last time we talked a little bit about hirerarchical endpoints, as an example, here is /students/<s_id>/applications, which gives all applications for a given student (I didn't have time to do this during the lecture, but there isn't really anything new in this endpoint):

@get('/students/<s_id>/applications')

def get_student_applications(s_id):

c = db.cursor()

c.execute(

"""

SELECT s_id, c_name, major, decision

FROM applications

JOIN students

USING (s_id)

WHERE s_id = ?

""",

[s_id]

)

found = [{"id": s_id,

"college": c_name,

"major": major,

"decision": decision}

for s_id, c_name, major, decision in c]

response.status = 200

return {"data": found}

Functional dependencies, closures and keys

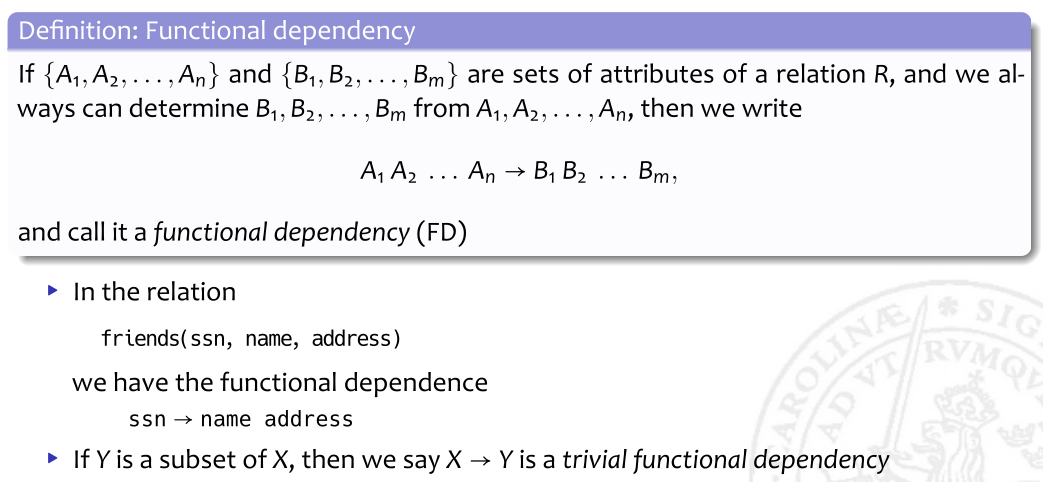

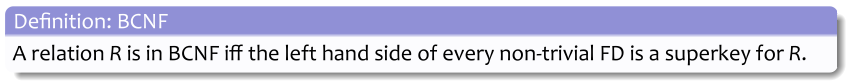

We then first had a look at the concept on redundancy, and some anomalies (see the slides), and then looked at the definition of a functional dependency:

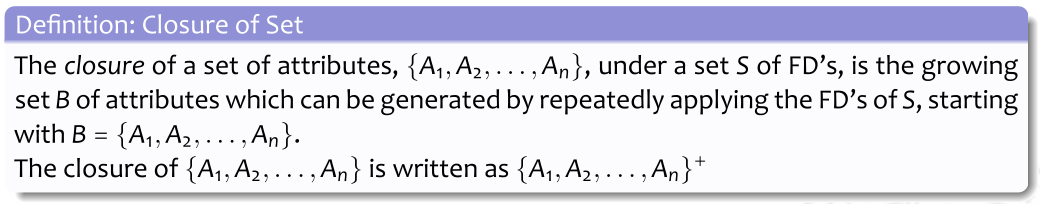

We then discussed closures:

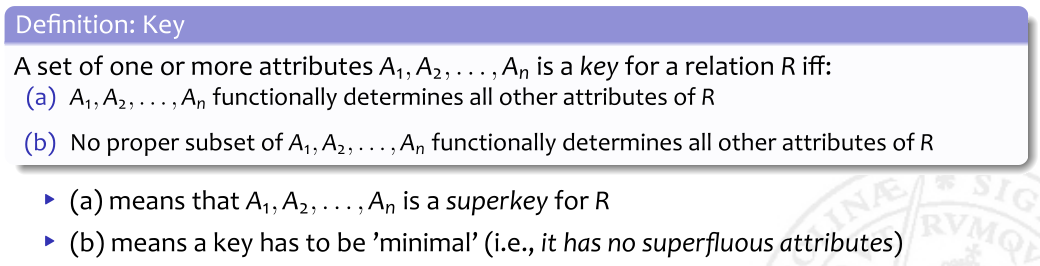

and keys:

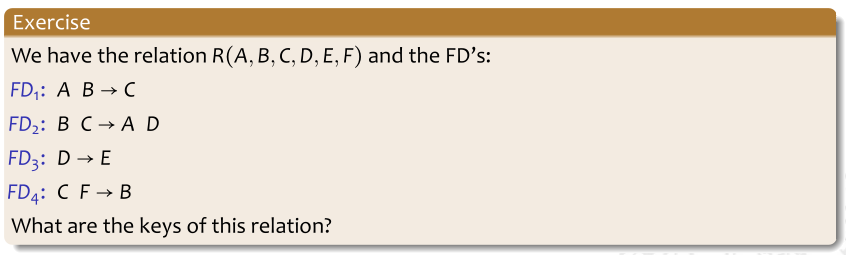

We used this to solve the following problem:

We first saw that the transitive closure of AB was ABCDE (there's no way to generate F), and we then tried to find the keys.

We first saw that F must be in any key, since it's not on the right hand side of any dependency.

But the transitive closure of F is just F, so it's not a key by itself.

We then tried all possible two attribute sets containing F, and found that CF generated all attributes, so it's a key.

{AF}+ = AF

{BF}+ = BF

{CF}+ = CFBADE = ABCDEF <- key!

{EF}+ = DFE

{DF}+ = EF

So there is a two-attribute key, but this doesn't mean that there can't be more keys – there could potentially be a three attribute set which is a key, and we're already seen that it must contain F, but for it to be minimal, it can't contain C (because any attributes beside CF would be superfluous), so we need to try:

{ABF}+ = ...

{ADF}+ = ...

{AEF}+ = ...

{BDF}+ = ...

{BEF}+ = ...

{DEF}+ = ...

To save time, I left as an exercise for you to calculate the closures of the three-attribute sets, and if you do it correctly you'll find another key.

But we're not necessarily done here, there might also be a four attribute set which is a key, so try to come up with all four attribute set who don't contain any of our previously found keys:

{....}+ = ...

So, we found one candidate keys, CF, and there will be another if you do the exercise above, and those are both minimal in the sense that nothing can be taken away from them for them to still be keys.

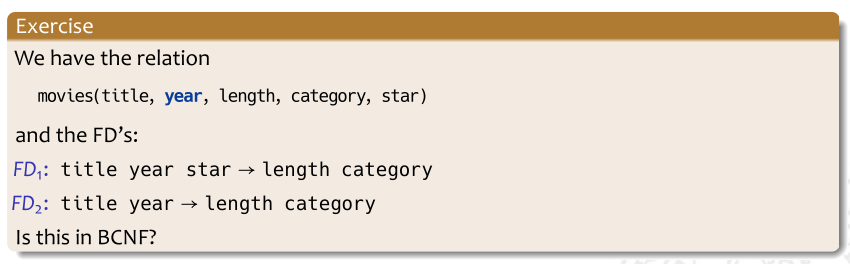

Normal forms, and normalizing to BCNF

Next we talked about normal forms (see the slides), and focused on BCNF, which is the normal form we normally strive for in this course:

The "iff" means "if-and-only-if", so it's a required, but also sufficient condition.

As an example, we looked at:

The functional dependencies asserts that a movie can only belong to one category, and we assumed this to be true when we solved the problem, although I had to agree that it's not really true in real life (unless we introduce special categories for genre-bending movies).

Since there are no ways to 'generate' either of title, year, or star, they must all belong to any key, and using them together, we can find all other attributes, which means that they're a key by themselves (and the only key).

But the the left hand side of FD2, (title, year), isn't a superkey, and that means that we're not in BCNF.

The point here is that since (title, year) isn't a key, we can have many rows with the same pair of values for title and year, and each time we get the same values for length and category – this is precisely the kind of redundancy which BCNF will help us avoid.

On Thursday we,ll see how we can 'normalize' this table into two tables which are in BCNF, which means that they're much easier to maintain (they'll have no redundancies based on functional dependencies).