EDAF75: Database technology

Session 6 – notes

Here are some notes for lecture 6 (the Thursday lecture in course week 3). I spent most of the time going through the slides and implementing parts of a simple REST server in Python – you can see the slides here, and the data I used can be downloaded here (it's a zipfile with a SQL script to create the college database, and a csv file with some extra applications).

Finishing the exercise from Monday

I started by finishing the example we began on Monday, I then left it as an exercise for you.

After the Monday lecture, the code in admit.py looked like this:

import sqlite3

import sys

db = sqlite3.connect('colleges.sqlite')

def main():

major, college = sys.argv[1:]

c = db.cursor()

c.execute(

'''

WITH

enrollments(enrollment) AS (

SELECT enrollment

FROM programs

WHERE major = ? AND c_name = ?

),

admissions(admitted) AS (

SELECT count()

FROM applications

WHERE major = ? AND c_name = ? AND

decision = 'Y'

)

SELECT enrollment, admitted

FROM enrollments

CROSS JOIN admissions;

''',

[major, college, major, college]

)

enrollment, admitted = c.fetchone()

print(f' {admitted} of {enrollment} already admitted')

c.execute(

'''

SELECT s_id,

s_name,

gpa,

rank() OVER (ORDER BY gpa DESC)

FROM applications

JOIN students USING (s_id)

WHERE major = ? AND c_name = ?

AND decision = 'N'

''',

[major, college]

)

for id, name, gpa, rank in c:

print(f' {rank:3d} {gpa:4.2f} - {id} ({name})')

count = int(input('How many do you want to admit? '))

# To be continued (see below)

main()

If you want to try this out yourself, you can download the data I used, and create a database with some more applications:

$ unzip lect-06-data.zip $ sqlite3 colleges.sqlite < setup-colleges.sql $ sqlite3 colleges.sqlite ".import --csv extra-applications.csv applications"

So, we now need a way to get the waitlist, and admit the first few people in it.

We talked a bit about how to go about it, and we said that one possibility is to have our Python code get the waitlist from SQL, and then iterate over the student ids from Python, doing one SQL call with UPDATE for each admitted student.

To do this, we could modify the code above slightly, and add a random element to the ordering in the last query – we can then use the result from a Python loop:

c.execute(

'''

SELECT s_id,

s_name,

gpa,

rank() OVER (ORDER BY gpa DESC, random())

FROM applications

JOIN students USING (s_id)

WHERE major = ? AND c_name = ?

AND decision = 'N'

''',

[major, college]

)

waitlist = [(rank, id, name, gpa) for id, name, gpa, rank in c]

for rank, id, name, gpa in waitlist:

print(f' {rank:3d} {gpa:4.2f} - {id} ({name})')

count = int(input('How many do you want to admit? '))

for _, id, _, _ in waitlist[:count]:

c.execute(

'''

UPDATE applications

SET decision = 'Y'

WHERE major = ? AND c_name = ? AND s_id = ?

''',

[major, college, id]

)

db.commit()

This works, but there are a lot of roundtrips between Python and SQL, and for some systems they can be costly (not for SQLite3 though, since it only communicates directly with the file system).

As a better alternative, we can do all the updating from SQL code – here is the code we came up with:

# ... as above ...

count = int(input('How many do you want to admit? '))

c.execute(

'''

WITH

waitlist(s_id, ranking) AS (

SELECT s_id, rank() OVER (ORDER BY gpa DESC, random())

FROM applications

JOIN students USING (s_id)

WHERE major = ? AND c_name = ? AND decision = 'N'

),

admitted(s_id) AS (

SELECT s_id

FROM waitlist

WHERE ranking <= ?

)

UPDATE applications

SET decision = 'Y'

WHERE s_id IN admitted AND major = ? AND c_name = ?

''',

[major, college, count, major, college]

)

db.commit()

BTW, here we get a pretty long list of values to insert into our query, there are other ways of doing it, one of them is to add the values in a dictionary, and then use their 'keys' inside the query:

c.execute(

'''

WITH

waitlist(s_id, ranking) AS (

SELECT s_id, rank() OVER (ORDER BY gpa DESC, random())

FROM applications

JOIN students USING (s_id)

WHERE major = :major AND c_name = :college AND decision = 'N'

),

admitted(s_id) AS (

SELECT s_id

FROM waitlist

WHERE ranking <= :count

)

UPDATE applications

SET decision = 'Y'

WHERE s_id IN admitted AND major = :major AND c_name = :college

''',

{

"major": major,

"college": college,

"count": count

}

)

Feel free to ask about this during any QA session (or during a lecture break).

Databases as part of larger infrastructure

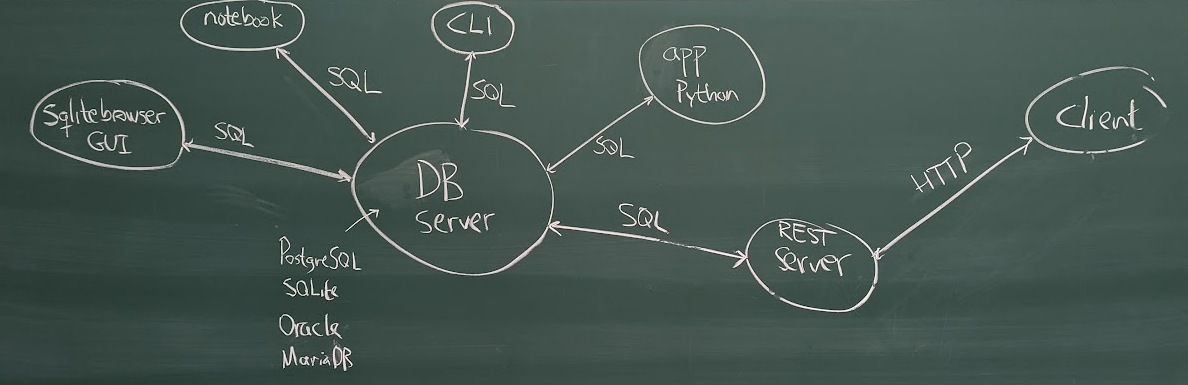

I then tried to illustrate how we can use a database server from various kinds of clients (notebooks, GUIs like sqlitebrowser, the sqlite3 command line interpreter, and Python programs like the one we wrote last time):

This time we added a program which itself will be a server (we'll call it a REST server, although it may be more accurate to call it a 'JSON over HTTP' server).

I waved my hands a bit, trying to explain how we could use HTTP (the same protocol which web browsers talk to their websites with) to send requests for various resources, and use JSON to specify data (hence 'JSON over HTTP').

The slides illustrate some details of the HTTP protocol, not because it's important for databases per se, but because this is a technique which is often used in conjunction with databases.

The major point of having our REST service is that it's a front end to our database, and we can use it to shield the database from the outside world. REST services are typically used from web apps, who call the service to get data to present in the browser.

During the course you'll have to implement two REST services of your own, one for lab 3, and one for the project – in both cases you'll do it in Python.

You don't need to learn how to design REST apis in this course, but there's a good website describing principles for designing a REST API – it's way beyond the scope of this course, but may give you some perspective.

A simple REST service implemented in Python/Bottle

There are many frameworks/libraries for implementing REST services in Python, in the course we're going to use Bottle, since it's a pretty simple library, and it allows us to focus on what matters most for the course (SQL).

So I started to implement some endpoints of a REST service in Python, using Bottle.

There are several different ways to install Python and Bottle on your own computer, I use uv, but you can easily google your way to a number of setups. I'll leave it to you how to handle the installation.

To create a directory for the lecture, and set up a Bottle service in it, I wrote (in the same kind of CLI we saw last time):

$ mkdir college-service && cd college-service $ uv init $ uv add bottle

I also copied the database I used for the example above into this new directory.

$ cp ../colleges.sqlite

I now created a file app.py using my text editor, and we began with the simlest possible service, which just answers GET calls to the endpoint /ping:

from bottle import get, post, request, response, run

HOST = 'localhost'

PORT = 4567

@get('/ping')

def get_ping():

response.status = 200

return 'pong'

run(host=HOST, port=PORT)

To run this, I used uv:

$ uv run app.py

With a regular Python installation I could've started it with:

$ python app.py

For this to work, the Bottle library must be installed (either globally, or locally).

The service runs on localhost, which is our own computer, and listens at port 4567 – I opened a new terminal window (the other one was busy running my server), and made a call from a client called curl:

$ curl -X GET http://localhost:4567/ping pong

I noted that the curl command does not have to run from the same directory as the server (indeed, I ran it from my home directory).

We then implemented some endpoints, such as:

GET /students, which returns all studentsGET /students/<s_id>, which returns the student with a given idGET /students, with any of two query parameters (nameandminGpa)

Next time we'll also implement:

POST /students, which adds a new student

You'll find our implementations of the first three endpoints below.

Looking for all students

During the lecture, I first implemented the regular "/students"-endpoint, using the function get_students():

from bottle import request, response, get, post, run

import sqlite3

db = sqlite3.connect('colleges.sqlite')

HOST = 'localhost'

PORT = 4567

@get('/ping')

def get_ping():

response.status = 200

return 'pong'

@get('/students')

def get_students():

c = db.cursor()

c.execute(

"""

SELECT s_id, s_name, gpa

FROM students

"""

)

found = [{'id': s_id,

'name': s_name,

'gpa': gpa} for s_id, s_name, gpa in c]

response.status = 200

return {'data': found}

run(host='localhost', port=PORT)

I tried to explain how the list comprehension where we picked values from our query result works, there is an attempt at another explanation near the bottom of this page.

The @get('/students') thingy just before the definition of get_students is a decorator, which Bottle uses to tie GET requests for the endpoint "/students" to the function get_students – it also ensures that Bottle transforms the return value of the function into something appropriate, in this case it will turn a Python dict a text representing a JSON object with the same content as the dict.

One thing which is a bit surprising is that Bottle doesn't handle lists as return values, but REST services (or JSON over HTTP) typically wrap their results inside an object with the field "data", so that's what the return statement does.

If we had been dead set on returning just a JSON list, we could have done so using Python's standard JSON package (import json and then json.dumps(found)), but the wrapped return value above is the prefered way to do it.

Looking for a specific student resource

Looking for a specific student using their s_id, we add the id to the endpoint URL (I showed you this during the lecture), and Bottle will extract id it into an argument to the decorated function:

@get('/students/<s_id>')

def get_student(s_id):

c = db.cursor()

c.execute(

'''

SELECT s_id, s_name, gpa

FROM students

WHERE s_id = ?

''',

[s_id]

)

found = [{'id': s_id,

'name': s_name,

'gpa': gpa} for s_id, s_name, gpa in c]

response.status = 200 if len(found) > 0 else 404

return {'data': found}

We can now find information about just one student, but we return a list (which is nice, since we only need to return an empty list in case there is no student with the given id).

$ curl -X GET http://localhost:4567/students/123

{"data": [{"id": 123, "name": "Amy", "gpa": 3.9}]}%

$ curl -X GET http://localhost:4567/students/124

{"data": []}%

We also tried this endpoint inside a tool called "insomnia" (the version I used is free), and from a browser (using http://localhost:4567/students/123 as url – GET is implicit when you send a browser request), but there are many alternatives.

Using query strings to find specific values

Sometimes we want to have a way to filter out specific values, if we want just all student with the name "Amy", we want to be able to use the call:

$ curl -X GET http://localhost:4567/students?name=Amy | jq

{

"data": [

{

"id": 123,

"name": "Amy",

"gpa": 3.9

},

{

"id": 654,

"name": "Amy",

"gpa": 3.9

}

]

}

The exact format of the curl arguments depends on where we write them, when I write the call above in the terminal window of my desktop computer (fish 4 shell running in ghostty) it looks as above, but when I paste the same text into zsh it adds some backslashes:

$ curl -X GET http://localhost:4567/students\?name\=Amy | jq

and the very old version of fish I have on my laptop (3.7) doesn't even allow me to write the command without apostrophes (that's why I got a weird error during the lecture and used insomnia instead).

So, YMMV, depending on what operating system you're on, and what command line client or tool you use.

BTW, the original output of the command was actually much 'messier' (everything on one line), but I piped it through the program jq, which makes it look much nicer (as above).

To make this query work, we need to update our /students endpoint, it could now potentially have query parameters.

The query parameters are sent as a part of the URL, and many of the symbols we might want to use in our queries, such as spaces, commas and periods, aren't allowed in a URL. Fortunately we can use URL encoding (also known as Percent-encoding), which is a standardized way of translating a string with 'illegal' characters into a safe string, and back again. As an example, using URL encoding we can translate the string

to be, or not to be

into

to%20be%2C%20or%20not%20to%20be

In Python we can import the quote and unquote functions from urllib.parse:

from urllib.parse import quote, unquote

which gives us quote to translate from regular text into 'safe' strings, and unquote to translate back to regular text again.

To add query parameters to our requests, we write an updated version of the getStudents method we saw above – now we have to check which query parameters are in request (for requests without parameters, it's going to work as before). One way to do this is to first create a query which is amenable to the addition of zero or more extra conditions.

So instead of

SELECT s_id, s_name, gpa FROM students

I added the seemingly nonsensical WHERE TRUE:

SELECT s_id, s_name, gpa FROM students WHERE TRUE

This is a very pragmatic trick, and the point of it is that we now can add zero or more lines with additional conditions:

SELECT s_id, s_name, gpa, size_hs

FROM students

WHERE TRUE

AND s_name = ?

AND gpa > ?

We can ask request for potential query parameters by just testing if they're defined – the expression

request.query.name

contains the value of the query parameter name, if it's set, or None if it's not set.

This is what we ended up with (the time was running out, so I din't add the minGpa test until afterwards):

@get('/students')

def get_students():

query = """

SELECT s_id, s_name, gpa

FROM students

WHERE TRUE

"""

params = []

if request.query.name:

query += "AND s_name = ?"

params.append(unquote(request.query.name))

if request.query.minGpa:

query += "AND gpa >= ?"

params.append(request.query.minGpa)

c = db.cursor()

c.execute(

query,

params

)

response.status = 200

found = [{"id": id,

"name": name,

"gpa": grade} for id, name, grade in c]

return {"data": found}

To use this, the caller must URL-encode her query parameters – for simple strings as above, it will make no difference:

$ curl -X GET http://localhost:4567/students?minGpa=3.9&name=Amy

but to look for "Obi wan", the encoding looks a bit different:

$ curl -X GET http://localhost:4567/students?minGpa=3.9&name=Obi%20wan

Posting data to the REST service

Since the time was up, we postponed this until the lecture on Monday.

How to extract values from a query in Python

Python has several features which simplifies working with query results and JSON objects a lot, some of them are:

- lists,

- list comprehensions,

- tuples,

- dictionaries, and

- the

jsonlibrary.

We can easily define a list with simple values, such as the smallest primes:

small_primes = [2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13]

If we wanted a list of the squares of these primes, we could write:

squares_of_small_primes = []

for p in small_primes:

squares_of_small_primes.append(p*p)

but this is verbose, and relies on mutable state. Python allows us to instead write this as:

squares_of_small_primes = [p*p for p in small_primes]

It means that we run the loop inside the list, and generates values which will be returned in one fell swoop – it's called a list comprehension (Python also have some very useful cousins to list comprehensions, such as set comprehensions, dictionary comprehensions, and generator comprehensions).

Another very useful feature is tuples, which allows us to pack related values in very flexible containers – let's say we wanted to have a list of some countries and their capitals, we could define it as:

geography = [("Sverige", "Stockholm"),

("Danmark", "Köpenhamn"),

("Norge", "Oslo")]

We can iterate through this list using a simple loop:

for (country, capital) in geography:

print(f"{country} har huvudstaden {capital}")

We don't even need the parenthesis around the tuple in the loop header:

for country, capital in geography:

print(f"{country} har huvudstaden {capital}")

We also have dictionaries, which are a very pragmatic version of the Maps we find in Java. We can define a dictionary with the names of the smallest integers

numbers = {0: "zero", 1: "one", 2: "two", 3: "three"}

for k in range(0,5):

print(f"{k} is {numbers.get(k, 'unknown')}")

which gives the output

0 is zero 1 is one 2 is two 3 is three 4 is unknown

By combining lists, tuples, list comprehensions and dictionaries, we can generate a list with dictionaries:

geography = [("Sverige", "Stockholm"),

("Danmark", "Köpenhamn"),

("Norge", "Oslo")]

nordic_capitals = [{"country": country,

"capital": capital} for country, capital in geography]

print(nordic_capitals)

which gives

[{'country': 'Sverige', 'capital': 'Stockholm'}, {'country': 'Danmark', 'capital': 'Köpenhamn'}, {'country': 'Norge', 'capital': 'Oslo'}]

and this is very close to the kind of JSON object we want to return from our REST calls.

If we import the json library, and use the json.dumps function, we can turn this into a JSON object directly:

import json

geography = [("Sverige", "Stockholm"),

("Danmark", "Köpenhamn"),

("Norge", "Oslo")]

nordic_capitals = [{"country": country,

"capital": capital} for country, capital in geography]

print(json.dumps(nordic_capitals))

We'll get:

[{"country": "Sverige", "capital": "Stockholm"}, {"country": "Danmark", "capital": "Köpenhamn"}, {"country": "Norge", "capital": "Oslo"}]

We can use this technique to convert the result of a sqlite3 query into a JSON object.

Common SELECT statements will give us lists like the geography list above

– let's say we use the query:

c = db.cursor()

c.execute(

"""

SELECT s_id, s_name, gpa

FROM students

"""

)

Our cursor would now contain a sequence of tuples, each containing three values (akin to the list of two-tuples we had above) – to generate a list of dictionaries with these values we could write:

found = [{"id": s_id,

"name": s_name,

"gpa": gpa} for s_id, s_name, gpa in c]

and we could use this to generate a JSON object using json.dumps, or let Bottle handle it (Bottle will, surprisingly, not convert list automatically, but we'll anyways wrap the result into another object first – more on that in the text above).