Lecture 4 – notes

Picking up where we left last time…

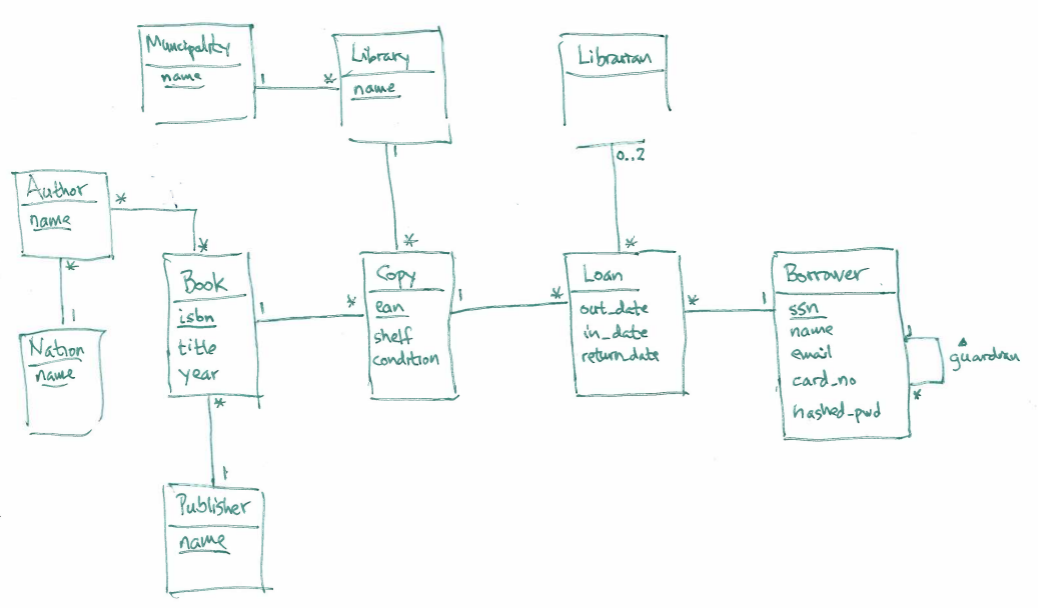

We first had a quick look at the model from Monday – we were almost finished (we need some more associations around Borrower, Library and Librarian, they're not in the diagram below), but added an entity set Author, which describes our authors.

Since each book can be witten by several authors, and each author can write several books, we have a *-* association between them:

Translating the college application model into tables

Defining tables

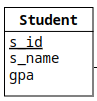

We then started working in a notebook for the lecture, and first saw how to translate simple entity sets like Student and College into tables – we had

and used the CREATE TABLE statement to define:

CREATE TABLE students ( s_id INT, s_name TEXT, gpa REAL, PRIMARY KEY (s_id) );

The entity set is written in singular, as Student, since it describes a single student, but the table will contain all students, so we define it as students (I commented that this is just a convention I've chosen, other people do it differently, just as my choice of using UPPERCASE for SQL commands is optional).

I suggest you try to run the code above in the notebook, and see what happens when you run SELECT * FROM students.

In case we want to redefine the table it can be useful to drop it before creating it again (the syntax is in the notebook, and can be seen in the SQLite documentation):

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS students; CREATE TABLE students ( s_id INT, s_name TEXT, gpa REAL, PRIMARY KEY (s_id) );

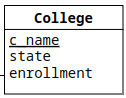

We then did the same for the entity set College:

and got:

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS colleges; CREATE TABLE colleges ( c_name TEXT, state TEXT, enrollment INT, PRIMARY KEY (c_name) );

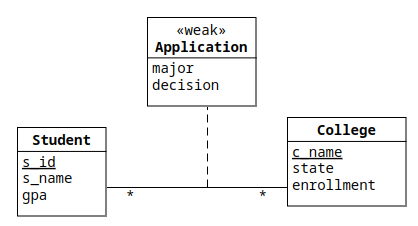

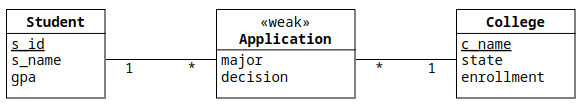

Then we had a look at the Application entity set – as we saw last time, we could write it either as an association class for the *-* between Student and College:

or as a standalone class between Student and College:

As a beginner, it's probably easier to understand the 'standalone' version (the second one), so we started there.

Hopefully it's obvious that major and decision should be attributes (columns) in our applications table (just as s_id, s_name and gpa were attributes in the students table), but we discussed how to implement the two *-1 associations emanating from Application.

Somehow we want each row in applications to reference one row in the students table, and one row in the colleges table, and the way to do it is to have one 'foreign key' for each table in the applications table.

The keys themselves are just the same kind of values as the corresponding key, but we also declare them in a FOREIGN KEY clause:

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS applications;

CREATE TABLE applications (

s_id INT,

c_name TEXT,

major TEXT,

decision CHAR DEFAULT ('N'),

PRIMARY KEY (s_id, c_name, major),

FOREIGN KEY (s_id) REFERENCES students(s_id),

FOREIGN KEY (c_name) REFERENCES colleges(c_name)

);

SELECT *

FROM applications;

We don't write out s_id and c_name in applications in the ER diagram, since they're already in there (as *-1 associations).

Defining our foreign keys ensures that the database protects us from obvious inconsistencies – if we have a row where s_id is 123, it will check that there is a row where s_id is 123 in the students table (in week 5 we'll get back to how to handle errors).

Unfortunately, for historical reasons, SQLite doesn't check foreign keys by default, but we can turn it on with a pragma:

PRAGMA foreign_keys = TRUE;

Inserting values

We then used the INSERT statement to insert some values in our database:

INSERT

INTO students

VALUES (123,'Amy',3.9),

(234,'Bob',3.6),

(345,'Craig',3.5),

(456,'Doris',3.9),

(543,'Craig',3.4),

(567,'Edward',2.9),

(654,'Amy',3.9),

(678,'Fay',3.8),

(765,'Jay',2.9),

(789,'Gary',3.4),

(876,'Irene',3.9),

(987,'Helen',3.7);

INSERT

INTO colleges

VALUES ('Stanford','CA',15000),

('Berkeley','CA',36000),

('MIT','MA',10000),

('Cornell','NY',21000);

INSERT

INTO applications

VALUES (123,'Stanford','CS','Y'),

(123,'Stanford','EE','N'),

(123,'Berkeley','CS','Y'),

(123,'Cornell','EE','Y'),

(234,'Berkeley','biology','N'),

(345,'MIT','bioengineering','Y'),

(345,'Cornell','bioengineering','N'),

(345,'Cornell','CS','Y'),

(345,'Cornell','EE','N'),

(678,'Stanford','history','Y'),

(987,'Stanford','CS','Y'),

(987,'Berkeley','CS','Y'),

(876,'Stanford','CS','N'),

(876,'MIT','biology','Y'),

(876,'MIT','marine biology','N'),

(765,'Stanford','history','Y'),

(765,'Cornell','history','N'),

(765,'Cornell','psychology','Y'),

(543,'MIT','CS','N');

Now we have the same database as we had during lecture 2, and I recommend that you try out some queries in the notebook.

Updating values

We can use the UPDATE statement to update rows in our tables, so we wrote some code to inflate the grades of all students who has applied for any major at a Californian college:

UPDATE students

SET gpa = min(1.05*gpa, 4.0)

WHERE s_id IN (

SELECT s_id

FROM applications

JOIN colleges USING (c_name)

);

To reset our database, we could use the INSERT statement again, but this time we need to tell the database what to do if we try to insert a row which 'collides' with an old key (in this case, all students will be in the students table already, so all s_id-values will lead to collisions).

This can be solved if we use the INSERT OR REPLACE statement:

INSERT OR REPLACE

INTO students

VALUES (123,'Amy',3.9),

(234,'Bob',3.6),

(345,'Craig',3.5),

(456,'Doris',3.9),

(543,'Craig',3.4),

(567,'Edward',2.9),

(654,'Amy',3.9),

(678,'Fay',3.8),

(765,'Jay',2.9),

(789,'Gary',3.4),

(876,'Irene',3.9),

(987,'Helen',3.7);

Deleting values

To delete values, we use the DELETE statement, we first used it to delete all students who hadn't applied for any major:

DELETE

FROM students

WHERE s_id NOT IN (

SELECT s_id

FROM applications

);

We tried it, and it worked.

We then tried to remove the rest of the students, but then we ran into problems with our foreign keys:

DELETE FROM students;

The reply from Jupyter was:

RuntimeError: (sqlite3.IntegrityError) FOREIGN KEY constraint failed [SQL: DELETE FROM students;] (Background on this error at: https://sqlalche.me/e/20/gkpj)

The problem is that removing the students would have rendered all applications invalid – in week 5 we'll see how to handle this automatically, but for now we could see that all students remained, which is a good thing (if we really want to remove a student, we have to first remove the student's applications).

Improving the design of the college application database

We discussed that the current design of our college application database didn't allow us to see all possible programs (i.e., which majors were available at which colleges), and how many students were allowed into each program.

To address this problem we enhanced our ER-model (we did this already last time), and got:

'

We talked about how to keep track of how many students each program allowed, and added the attribute

enrollment to our Program class.

We first defined two new tables:

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS majors; CREATE TABLE majors ( major TEXT, full_name TEXT, credits TEXT, PRIMARY KEY (major) ); DROP TABLE IF EXISTS programs; CREATE TABLE programs ( major TEXT, c_name TEXT, enrollment INT, PRIMARY KEY (major, c_name), FOREIGN KEY (major) REFERENCES majors(major), FOREIGN KEY (c_name) REFERENCES colleges(c_name) );

We started with the majors, since they're the most basic entities here, but if we want to run these definitions a second time, we would have to reorder, since we can't drop the majors table until we've already removed any foreign keys in the programs table.

Now we saw that we can populate these tables using another version of the INSERT statement – we first put all the majors we can find in the applications table into majors:

INSERT

INTO majors(major, full_name, credits)

SELECT DISTINCT major, 'no description', 300

FROM applications;

At this point the time was running low, so I continued with the slides, but I recommended you to try to write code to add all programs we could find in applications into programs, and assume that the enrollment was three times bigger than the current enrollment:

INSERT

INTO programs(major, c_name, enrollment)

SELECT major, c_name, 3*count()

FROM applications

WHERE decision = 'Y'

GROUP BY major, c_name

);

One problem here is that some programs haven't yet accepted any applications, and to add them with the enrollment set to 5, we could use an INSERT statement using a CTE:

WITH

active_programs(major, c_name) AS (

SELECT DISTINCT major, c_name

FROM applications

WHERE decision = 'Y'

),

pending_programs(major, c_name) AS (

SELECT DISTINCT major, c_name

FROM applications

WHERE (major, c_name) NOT IN active_programs

)

INSERT

INTO programs(major, c_name, enrollment)

SELECT major, c_name, 5

FROM pending_programs;

When we have a look, we get:

major c_name enrollment -------------- -------- ---------- CS Berkeley 6 CS Cornell 3 CS MIT 5 CS Stanford 6 EE Cornell 3 EE Stanford 5 bioengineering Cornell 5 bioengineering MIT 3 biology Berkeley 5 biology MIT 3 history Cornell 5 history Stanford 6 marine biology MIT 5 psychology Cornell 3

Here we see that Cornell is the only college which hosts a psychology program, but in the current version of our database (where the applications only checks that c_name is a real college), we can easily add an application for psychology at MIT:

INSERT INTO applications(s_id, major, c_name) VALUES (123, 'psychology', 'MIT');

So, to alleviate this, we have to update the applications table, and make sure that the pair major and c_name are in the program table.

We do that by altering the applications table (I mentioned quickly that we actually can alter our tables, using the ALTER TABLE command, but here we just replace the table from scratch), so we replace:

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS applications;

CREATE TABLE applications (

s_id INT,

c_name TEXT,

major TEXT,

decision CHAR DEFAULT ('N'),

PRIMARY KEY (s_id, c_name, major),

FOREIGN KEY (s_id) REFERENCES students(s_id),

FOREIGN KEY (c_name) REFERENCES colleges(c_name)

);

with:

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS applications;

CREATE TABLE applications (

s_id INT,

c_name TEXT,

major TEXT,

decision CHAR DEFAULT ('N'),

PRIMARY KEY (s_id, c_name, major),

FOREIGN KEY (s_id) REFERENCES students(s_id),

FOREIGN KEY (major, c_name) REFERENCES programs(major, c_name)

);

We can now insert the applications again (we don't need INSERT OR REPLACE, since we just recreated the whole table):

INSERT

INTO applications

VALUES (123,'Stanford','CS','Y'),

(123,'Stanford','EE','N'),

(123,'Berkeley','CS','Y'),

(123,'Cornell','EE','Y'),

(234,'Berkeley','biology','N'),

(345,'MIT','bioengineering','Y'),

(345,'Cornell','bioengineering','N'),

(345,'Cornell','CS','Y'),

(345,'Cornell','EE','N'),

(678,'Stanford','history','Y'),

(987,'Stanford','CS','Y'),

(987,'Berkeley','CS','Y'),

(876,'Stanford','CS','N'),

(876,'MIT','biology','Y'),

(876,'MIT','marine biology','N'),

(765,'Stanford','history','Y'),

(765,'Cornell','history','N'),

(765,'Cornell','psychology','Y'),

(543,'MIT','CS','N');

and this time

INSERT INTO applications(s_id, major, c_name) VALUES (123, 'psychology', 'MIT');

would fail:

RuntimeError: (sqlite3.IntegrityError) FOREIGN KEY constraint failed [SQL: INSERT INTO applications(s_id, major, c_name) VALUES (123, 'psychology', 'MIT');] (Background on this error at: https://sqlalche.me/e/20/gkpj)

Translating our model into a database

In the slides I had some 'recipes' for translating an ER model into tables in a relational database, we started out by looking at the 'obvious' parts of some of the 'obvious' tables (i.e., each entity set is translated into a corresponding table, and each attribut is translated into a column in the table).

During the lecture I only wrote a few tables, to illustrate some points, here I've first written the obvious parts of all entity sets – I've also defined a primary key where we can (there's no good key in the loans table at the moment):

-- This is only the first iteration, more will be added below CREATE TABLE authors ( author_name TEXT, nationality TEXT, PRIMARY KEY (author_name) ); CREATE TABLE books ( isbn TEXT, year INT, title TEXT, PRIMARY KEY (isbn) ); CREATE TABLE copies ( copy_ean TEXT, shelf TEXT, condition INT, PRIMARY KEY (copy_ean) ); CREATE TABLE libraries ( library_name TEXT, muncipality TEXT, PRIMARY KEY (library_name) ); CREATE TABLE librarian ( librarian_id TEXT, librarian_name TEXT, PRIMARY KEY (librarian_id) ); CREATE TABLE loans ( out_date DATE, last_in_date DATE, return_date DATE ); CREATE TABLE borrower ( card_id TEXT, ssn TEXT, name TEXT, email TEXT, hashed_pwd TEXT, PRIMARY KEY (card_id) );

During the lecture we talked about how to implement the *-1 from Copy to Book, and we could use exactly the same technique as we saw with the applications table above (i.e., a foreign key):

CREATE TABLE copies ( copy_ean TEXT, shelf TEXT, condition INT, isbn TEXT, PRIMARY KEY (copy_ean), FOREIGN KEY (isbn) REFERENCES books(isbn) );

Now we can use a JOIN if we want to get information about the book a copy refers to – let's say we are given an ean code, and want the corresponding title and year:

SELECT title, year

FROM copies

JOIN books USING (isbn)

WHERE copy_ean = '...';

In the same vein, we could add foreign keys to the tables copies (we also need to link them to libraries), loans, and borrowers:

-- Now with added foreign keys, but we still need more... CREATE TABLE copies ( copy_ean TEXT, shelf TEXT, condition INT, isbn TEXT, PRIMARY KEY (copy_ean), FOREIGN KEY (isbn) REFERENCES books(isbn) ); CREATE TABLE librarians ( librarian_id TEXT, librarian_name TEXT, library_name TEXT, PRIMARY KEY (librarian_id), FOREIGN KEY (library_name) REFERENCES libraries(library_name) ); CREATE TABLE loans ( copy_ean TEXT, card_id TEXT, out_date DATE, last_in_date DATE, return_date DATE, PRIMARY KEY (copy_ean, card_id, out_date), FOREIGN KEY (copy_ean) REFERENCES copies(copy_ean), FOREIGN KEY (card_id) REFERENCES borrowers(card_id) ); CREATE TABLE borrowers ( card_id TEXT, ssn TEXT, name TEXT, email TEXT, hashed_pwd TEXT, library_name TEXT, PRIMARY KEY (card_id), FOREIGN KEY (library_name) REFERENCES libraries(library_name) );

Since a borrower could potentially have library cards at many libraries, the primary key in the borrowers table can't be just ssn. We can use the tuple (ssn, library_name), but easier is to just use the card_id (which is what I did above).

In the loans table, our foreign keys to copies and borrowers help us getting a key (we had none above), but since a borrower can borrow the same copy many times, we also need the date of the loan to make it unique (assuming no one in their right mind borrows the same copy several times in a day… – in that case we could instead use an invented key).

To simplify things here, I haven't implemented the foreign keys to Librarian in the ER-diagram above (we could have one out_librarian_id for the librarian handling the borrowing of the copy, and one in_librarian_id for the librarian handling the returning of the book).

Exercise 1: Write a query which shows the title and year of all books the borrower with the ssn '20000101-1234' has borrowed at 'Lunds stadsbibliotek' (there is an answer at the end of this page, but you should definitely try to write the query yourself before looking at the answer!).

During the lecture we talked about how to implement a *-* association, and I hope it was clear to you why we couldn't just let each table have a foreign key to the other (we can only do that if we're referencing just one element in the other table, here we're potentially referencing many).

So we came up with join tables (see the slides), and we connected the authors table and books table with:

CREATE TABLE authorships ( author_name TEXT, isbn TEXT, PRIMARY KEY (author_name, isbn), FOREIGN KEY (author_name) REFERENCES authors(name), FOREIGN KEY (isbn) REFERENCES books(isbn) );

We also talked a bit about how to implement guardians for children – one way is to have the guardian's card-id as a foreign key:

CREATE TABLE borrowers ( card_id TEXT, ssn TEXT, name TEXT, email TEXT, hashed_pwd TEXT, library_name TEXT, guardian_card_id TEXT, PRIMARY KEY (card_id), FOREIGN KEY (library_name) REFERENCES libraries(library_name), FOREIGN KEY (guardian_card_id) REFERENCES borrowers(card_id) );

This works fine, and would mean that everyone who doesn't have a guardian will have their guardian_card_id as NULL (a foreign key is allowed to be NULL, it's only when it isn't NULL that the database checks that it refers to a valid row in the foreign table).

To get the name of a guardian with this implementation is a bit tricky – we need to join the table borrowers with itself.

This is called a self join, and it will introduce potential naming conflicts (see the notebook for lecture one, specifically the section about correlated subqueries).

To list the names of all children and their guardians, we can use the following query:

SELECT borrowers.name, guardians.name

FROM borrowers

JOIN borrowers AS guardians

ON borrowers.guardian_card_id = guardians.card_id

ORDER BY borrowers.name;

We want to join each row in the borrowers table where guardian_card_id isn't NULL with the corresponding row where card_id is the guardian_card_id of the original row.

To do this, we need to 'rename' the table of the guardian borrowers, in the code above I call it 'guardians', and then the query works.

But since the guardians table (which is the same as the borrowers table) have the column name, I must be specific about which name I'm referring to.

We can introduce the alias children for the 'outer' table (the table in which we look for rows with references to guardians):

SELECT children.name, guardians.name

FROM borrowers AS children

JOIN borrowers AS guardians ON children.guardian_card_id = guardians.card_id

ORDER BY children.name;

but I'm not sure this makes the query easier to understand (but YMMV).

An alternative would be to introduce a separate table with guardians (it would make sense if we have only few children in our database, and don't want all the NULL guardians hanging around):

CREATE TABLE guardians ( card_id TEXT, guardian_card_id TEXT, PRIMARY KEY (card_id), FOREIGN KEY (card_id) REFERENCES borrowers(card_id), FOREIGN KEY (guardian_card_id) REFERENCES borrowers(card_id) );

The 'rules' above will take us quite far when we translate an ER model into a relational database:

- an entity set will become a table

- a

*-1('many-to-one') association will become a foreign key on the*side of the association - a

*-*('many-to-many) association will become a new (join) table

For those *-* associations with an association class, the attributes of the association class will become attributes in the join table.

Exercise 2: Write a query to find the names and nationalities of the three most borrowed authors (answer below).

We then looked at some kinds of association which requires careful thought (see the slides), and three methods to implement inheritance (see the slides).

We concluded by looking at how to insert, update and delete data in our database – see the links above, and the slides.

If you have any questions about what we did, please go to Moodle and sign up for the QA session next week.

Solutions to exercises

Exercise 1

We need to join several tables: we start at the loans, then we need to:

- add information about the copy (to get the isbn code), so we

JOIN copies, using theean_code, which is in bothloansandcopies - add information about the book (to get its title and year), so we

JOIN books, using theisbncode, which is incopiesandbooks - add information about the borrowers (to get the ssn and library), so we

JOIN borrowersusing the card-id:

SELECT title, year

FROM loans

JOIN copies USING (copy_ean)

JOIN books USING (isbn)

JOIN borrowers USING (card_id)

WHERE ssn = '20000101-1234' AND

library_name = 'Lunds stadsbibliotek';

Exercise 2

Now we need to join even more tables, and then to group on the author names (which, amazingly!, were unique):

SELECT author_name, nationality, count()

FROM loans

JOIN copies USING (copy_ean)

JOIN books USING (isbn)

JOIN authorships USING (isbn)

JOIN authors USING (author_name)

GROUP BY author_name

ORDER BY count() DESC

LIMIT 3;