Lecture 5 – notes

This is a short description of what we did during lecture 5. I spent most of the time going through examples which I hope can be of help to you when you're about to solve lab 3 and the project – the slides are here.

Event sourcing

First we discussed ways to implement bank accounts – one simple way is to just keep the state of an account in a mutable attribute:

class Account { private int accountNumber; private double balance; public void deposit(double amount) { balance += amount; } public double withdraw(double amount) { var actual_amount = Math.min(amount, balance); balance -= actual_amount; return actual_amount; } public double balance() { return balance; } }

This is conceptually very simple, but there are some drawbacks:

- We know the balance of the account, but we don't know why it is the way it is.

- To update the account, we need to make sure that no one else updates it at the same time, so we need to use some kind of lock.

Because of this, it's become commonplace to save state updates instead of the state itself – in the case of bank accounts we would save all transfers, and then calculate the balance by going through all transfers (we could also 'cache' the balance at some point in time, and then just look at transfers after it). This is called event sourcing, and it gives us the account's history, and allows us to explain why we have the current balance. It also makes it 'cheaper' to alter the state of the accounts, we only need to add new transfers (we'll talk more about this in a few weeks time).

In lab 2 you'll need to think about how to keep track of the number of available seats for a performance – there are several ways, one of them is using event sourcing.

About DBMS's and SQLite

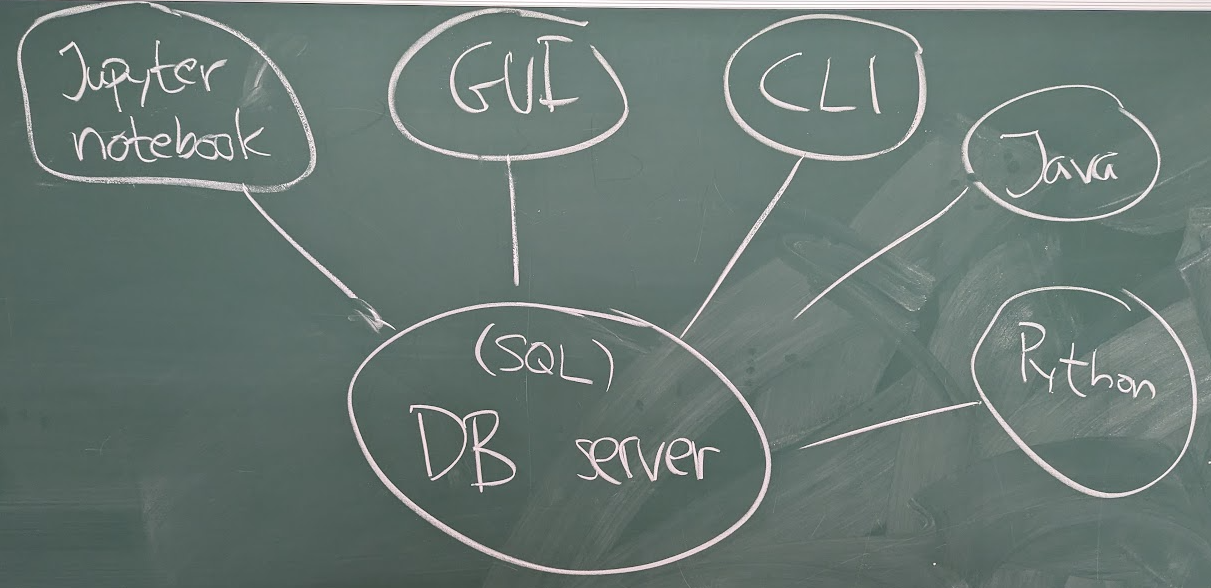

We then looked a drawing illustrating how we can use a database server:

I said that a DBMS normally runs as a server, and we talked about different ways of communicating with our database server:

- Using a notebook, such as the Jupyter notebooks we've used for lectures and lab 1.

- Using some kind of dedicated graphical client (a GUI), such as sqlitebrowser – I showed it to you briefly.

- Using a command line SQL-client, such as

psqlfor PostgreSQL, orsqlite3for SQLite (SQLite doesn't really run as a server, but when we run the command line client, it looks like it). - Using a program written in a traditional language, such as Java, or Python.

- Using some kind of microservice (typically REST) – this is just an example of the previous category, but it's very common, and they're typically used as backends for various web frontends – we'll return to this on Thursday (and on lab 3 and the project).

Using SQLite from a command line client

After the lecture I got some questions about what programs I was using, and it made me realize that some of you are not used to working with a command line interpreter (CLI) – I'd be happy to show you, and answer any question about it during the QA sessions.

On the screen for this part of the lecture I had two windows:

To the left I had a text editor (you can use any good text editor for writing SQL and Python code, I think VS Code is a safe bet – personally I use Emacs, and it's great, but it comes with some big caveats).

In the text editor I edited the SQL script (

setup.sql), and the Python programs (list-applications.py,inflate-grades.pyandadmit.py).- To the right I had a window in which I ran a command line interpreter (CLI) – it is a program which reads commands and executes programs (this program is often called a shell, and there are many to choose from, and the're very similar to each other – if you're running Windows you can use PowerShell, on Mac you can use whatever runs in your Terminal program, and if you're on Linux (as I am), you can use

bash,zsh,fish, or whatever).

I started the SQLite 'client' by issuing the command sqlite3 in my CLI (the rightmost window) – first I did it without giving any filename:

$ sqlite3 SQLite version 3.49.1 2025-02-18 13:38:58 Enter ".help" for usage hints. Connected to a transient in-memory database. Use ".open FILENAME" to reopen on a persistent database. sqlite>

Changes we do here will just be saved to an in-memory database, and we

would lose all our data when we exited (unless we explicitly save it,

see below).

To use a specific file to save our database, we just enter it as we start sqlite3:

$ sqlite3 colleges.sqlite

SQLite version 3.49.1 2025-02-18 13:38:58

Enter ".help" for usage hints.

sqlite>

Here we can do two different kinds of things:

- We can enter SQL commands – these are the common suspects,

SELECT,INSERT,UPDATE,CREATE TABLE, etc. We can enter SQLite commands – these are commands for reading from files, saving to files, etc, they're all prefixed by a

., so to read a database from the filecolleges.sqlite(from lecture 2), we write (sqlite>is just the prompt):sqlite> .open colleges.sqliteThere are many useful

sqlite3commands, during the lecture I used:.schema, which shows how our tables are defined.print, which prints a message when we run a script.mode, which alters the output format of our queries (we tried columns, boxes and html).drop(see below)

During lecture 4, we looked at an example with college applications, they are in the tables students, colleges, majors, programs, and applications, and we can use the sqlite3 command .dump to see SQL statements which would define the same tables, and the data in them:

$ sqlite3 colleges.sqlite SQLite version 3.49.1 2025-02-18 13:38:58 Enter ".help" for usage hints. sqlite> .dump PRAGMA foreign_keys=OFF; BEGIN TRANSACTION; CREATE TABLE students ( s_id INT, s_name TEXT, gpa REAL, PRIMARY KEY (s_id) ); INSERT INTO students VALUES(123,'Amy',3.899999999999999912); INSERT INTO students VALUES(234,'Bob',3.600000000000000088); INSERT INTO students VALUES(345,'Craig',3.5); INSERT INTO students VALUES(456,'Doris',3.899999999999999912); INSERT INTO students VALUES(543,'Craig',3.399999999999999912); INSERT INTO students VALUES(567,'Edward',2.899999999999999912); INSERT INTO students VALUES(654,'Amy',3.899999999999999912); INSERT INTO students VALUES(678,'Fay',3.799999999999999823); INSERT INTO students VALUES(765,'Jay',2.899999999999999912); INSERT INTO students VALUES(789,'Gary',3.399999999999999912); INSERT INTO students VALUES(876,'Irene',3.899999999999999912); INSERT INTO students VALUES(987,'Helen',3.700000000000000177); CREATE TABLE colleges ( c_name TEXT, state TEXT, enrollment INT, PRIMARY KEY (c_name) ); INSERT INTO colleges VALUES('Stanford','CA',15000); INSERT INTO colleges VALUES('Berkeley','CA',36000); INSERT INTO colleges VALUES('MIT','MA',10000); INSERT INTO colleges VALUES('Cornell','NY',21000); CREATE TABLE majors ( major TEXT, full_name TEXT, credits TEXT, PRIMARY KEY (major) ); INSERT INTO majors VALUES('CS','Computer Science','300'); INSERT INTO majors VALUES('EE','Electrical Engineering','300'); INSERT INTO majors VALUES('bioengineering','Bioengineering','300'); INSERT INTO majors VALUES('biology','Biology','300'); INSERT INTO majors VALUES('history','History','300'); INSERT INTO majors VALUES('marine biology','Marine Biology','300'); INSERT INTO majors VALUES('psychology','Psychology','300'); CREATE TABLE programs ( major TEXT, c_name TEXT, enrollment INT, PRIMARY KEY (major, c_name), FOREIGN KEY (major) REFERENCES majors(major), FOREIGN KEY (c_name) REFERENCES colleges(c_name) ); INSERT INTO programs VALUES('CS','Berkeley',6); INSERT INTO programs VALUES('CS','Cornell',3); INSERT INTO programs VALUES('CS','MIT',5); INSERT INTO programs VALUES('CS','Stanford',6); INSERT INTO programs VALUES('EE','Cornell',3); INSERT INTO programs VALUES('EE','Stanford',5); INSERT INTO programs VALUES('bioengineering','Cornell',5); INSERT INTO programs VALUES('bioengineering','MIT',3); INSERT INTO programs VALUES('biology','Berkeley',5); INSERT INTO programs VALUES('biology','MIT',3); INSERT INTO programs VALUES('history','Cornell',5); INSERT INTO programs VALUES('history','Stanford',6); INSERT INTO programs VALUES('marine biology','MIT',5); INSERT INTO programs VALUES('psychology','Cornell',3); CREATE TABLE applications ( s_id INT, c_name TEXT, major TEXT, decision CHAR DEFAULT ('N'), PRIMARY KEY (s_id, c_name, major), FOREIGN KEY (s_id) REFERENCES students(s_id), FOREIGN KEY (major, c_name) REFERENCES programs(major, c_name) ); INSERT INTO applications VALUES(123,'Stanford','CS','Y'); INSERT INTO applications VALUES(123,'Stanford','EE','N'); INSERT INTO applications VALUES(123,'Berkeley','CS','Y'); INSERT INTO applications VALUES(123,'Cornell','EE','Y'); INSERT INTO applications VALUES(234,'Berkeley','biology','N'); INSERT INTO applications VALUES(345,'MIT','bioengineering','Y'); INSERT INTO applications VALUES(345,'Cornell','bioengineering','N'); INSERT INTO applications VALUES(345,'Cornell','CS','Y'); INSERT INTO applications VALUES(345,'Cornell','EE','N'); INSERT INTO applications VALUES(678,'Stanford','history','Y'); INSERT INTO applications VALUES(987,'Stanford','CS','Y'); INSERT INTO applications VALUES(987,'Berkeley','CS','Y'); INSERT INTO applications VALUES(876,'Stanford','CS','N'); INSERT INTO applications VALUES(876,'MIT','biology','Y'); INSERT INTO applications VALUES(876,'MIT','marine biology','N'); INSERT INTO applications VALUES(765,'Stanford','history','Y'); INSERT INTO applications VALUES(765,'Cornell','history','N'); INSERT INTO applications VALUES(765,'Cornell','psychology','Y'); INSERT INTO applications VALUES(543,'MIT','CS','N'); COMMIT; sqlite>

We saw that we can also run SQL commands and SQLite commands given as command line parametrs – this enabled me to write:

$ sqlite3 colleges.sqlite ".dump" > create-college.sql

which created a simple textfile create-college.sql with the SQL statements above (the > is a redirection command, which takes the output of one command and saves it in a text file).

Given this file we could create a new database, with only the five tables above (now using <, which sends the content of a text file as input to another command):

$ sqlite3 colleges.sqlite < create-colleges.sql

and we could then see all the students:

$ sqlite3 colleges.sqlite

SQLite version 3.49.1 2025-02-18 13:38:58

Enter ".help" for usage hints.

sqlite> SELECT * FROM students;

s_id s_name gpa

---- ------ ---

123 Amy 3.9

234 Bob 3.6

345 Craig 3.5

456 Doris 3.9

543 Craig 3.4

567 Edward 2.9

654 Amy 3.9

678 Fay 3.8

765 Jay 2.9

789 Gary 3.4

876 Irene 3.9

987 Helen 3.7

sqlite>

We then used the text editor (to the left of the screen) to write a script which showed the names and grades for all students who had applied for Computer Science at Stanford.

I wrote it in a text file called list-applications.sql, and the SQL code was:

SELECT s_id, s_name, gpa FROM applications JOIN students USING (s_id) WHERE major = 'CS' AND c_name = 'Stanford' ORDER BY random();

I ran this by issuing the command sqlite3 colleges.sqlite < list-students.sql in the CLI window (on the right side of the screen):

$ sqlite3 colleges.sqlite < queries.sql ┌──────┬────────┐ │ s_id │ s_name │ ├──────┼────────┤ │ 123 │ Amy │ │ 876 │ Irene │ │ 987 │ Helen │ └──────┴────────┘

In lab 2 you'll have to create your own database file, and then sqlite3 will be invaluable.

Calling SQLite from Python

SQL is great for doing queries, inserts and updates of a database, but it's highly specialized for those purposes – it would be a nightmare to write traditional programs using SQL.

So we want a way to write code in some other language, and have it use SQL for what it's good for – in this course we'll use Python, which has great support for calling SQL.

In Python's standard library, there is a package called sqlite3, and it allows us to create a Connection to a database, and then creating a Cursor working with the database (sending queries and updates).

To use a SQLite3 database colleges.sqlite in Python we can import the sqlite3 library, and just write:

import sqlite3 db = sqlite3.connect('colleges.sqlite')

Now db is connected to our database, and we can create a cursor in which we can execute SQL statements using the execute command:

c = db.cursor()

We wrote a Python program which took a major and a college name as input, and then ran the same query as we saw above:

import sqlite3 import sys db = sqlite3.connect('colleges.sqlite') def main(): major, college = sys.argv[1:] c = db.cursor() c.execute( ''' SELECT s_id, s_name, gpa FROM applications JOIN students USING (s_id) WHERE major = ? AND c_name = ? ORDER BY random(); ''', [major, college] ) for id, name, gpa in c: print(f' {id}: {name} ({gpa})') main()

(I wanted to introduce the idea of randomness in the output, as a preparation for an upcoming example, that's why we wrote ORDER BY random() in the query).

The question marks in the query are values we send into our query, and they are put in a list as the second argument to the c.execute() method.

The result of the c.execute() statement is that the cursor c will be an iterator over tuples with the results of the SELECT statement – in this case we get 3-tuples with ids, names, and gpas, and we can unpack them with (as above):

for id, name, gpa in c: print(f' {id}: {name} ({gpa})')

We ran it as (I'm using uv to run my Python programs, but you can use any Python installation you want):

$ uv run list-applications.py CS Stanford 987: Helen (3.7) 123: Amy (3.9) 876: Irene (3.9)

At least I think it's hard to imagine a simpler way to call SQL code from another language!

As an example of updating the database, we wrote a small program which inflates the grades of students applying to programs in a given state. The program is meant to run as:

$ uv run inflate-grades.py CA

So, we let the user enter the state in question as a command line argument:

import sqlite3 import sys db = sqlite3.connect('colleges.sqlite') def main(): state = sys.argv[1] c = db.cursor() c.execute( ''' UPDATE students SET gpa = min(4.0, gpa * 1.04) WHERE s_id IN ( SELECT s_id FROM applications JOIN colleges USING (c_name) WHERE state = ? ) ''', [state] ) db.commit() main()

In the previous program, we just wanted to fetch data from our database, but this time we want to update it – to do that we need to do a commit on our connection, so we call db.commit() (it's the end of a transaction, and we'll talk about transactions in a couple of weeks time).

Near the end of the lecture we started to write a program which lets administrators admit students into programs. We first fetched the maximum enrollment and the number of admitted students:

import sqlite3 import sys db = sqlite3.connect('colleges.sqlite') def main(): major, college = sys.argv[1:] c = db.cursor() c.execute( ''' SELECT enrollment FROM programs WHERE major = ? AND c_name = ? ''', [major, college] ) enrollment, = c.fetchone() c.execute( ''' SELECT count() FROM applications WHERE major = ? AND c_name = ? AND decision = 'Y' ''', [major, college] ) admitted, = c.fetchone() print(f' {admitted} of {enrollment} already admitted') main()

I was asked if we really needed two separate queries for doing this, and I said that there is a 'cleverer' way of doing it using CTE:s and a CROSS JOIN – I promised to show it in these notes, so here we go:

import sqlite3 import sys db = sqlite3.connect('colleges.sqlite') def main(): major, college = sys.argv[1:] c = db.cursor() c.execute( ''' WITH enrollments(enrollment) AS ( SELECT enrollment FROM programs WHERE major = ? AND c_name = ? ), admissions(admitted) AS ( SELECT count() FROM applications WHERE major = ? AND c_name = ? AND decision = 'Y' ) SELECT enrollment, admitted FROM enrollments CROSS JOIN admissions; ''', [major, college, major, college] ) enrollment, admitted = c.fetchone() print(f' {admitted} of {enrollment} already admitted') main()

Observe that we need to repeat the major and c_name in the c.execute call, since they're needed in each of the CTE:s (there are four question marks).

Also observe that each of the CTE:s return just a single row, so the cross join is just one row, with the combined results of the subqueries.

We then continued by listing the students on the waitlist, and came up with:

c.execute(

'''

SELECT s_id,

s_name,

gpa,

rank() OVER (ORDER BY gpa DESC)

FROM applications

JOIN students USING (s_id)

WHERE major = ? AND c_name = ?

AND decision = 'N'

''',

[major, college]

)

for id, name, gpa, rank in c:

print(f' {rank:3d} {gpa:4.2f} - {id} ({name})')

We discussed whether to use rank() or row_number() in our window function, in the exercise below I'll argue that rank() could be the most logical choice.

Exercise: At this point, I decided to leave the implementation of the remainder of the program as an exercise until Thursday – we'll finish it at the start of the lecture, and I'd encourage you to have a try on your own before Thursday.

What we want is for the program to list all students on the waitlist as above, and to then ask how many of the students to admit.

The program should then update the applications table, and admit the top candidates on the waitlist (i.e., those with the highest gpa).

In case there is a tie (several with the same gpa), I think the program should randomly pick some of the applicants (that's why I introduced the random() function above) – before we do that, it seems reasonable to have all tied students listed with the same 'rank' (so rank() would be better than row_number() in the output above).